The President of the University of Pennsylvania, Elizabeth Magill, has resigned in the wake of her testimony before Congress about university responses to campus antisemitism.

This is terrible news. To be sure, I don't think Magill is obligated to stay in a position where she feels she either can't be effective or can't function; she has no obligation to stick things out in what I can only imagine is right now an impossibly toxic atmosphere. But still, Magill deserved better; she said absolutely nothing wrong in her testimony. Yet the bad faith grandstanding of the likes of Elise Stefanik -- an antisemitic conspiracy-mongerer in her own right -- has claimed a high-profile victim.

I published my post Thursday before reading Ken White's more colorful response to those smearing Magill, but I endorse it in full. There have definitely been other prominent free speech advocates who have taken the right line here, including Eugene Volokh and David Lat.

But others are not rising to the moment. I flagged in my last post Keith Whittington for wrongly and misleadingly making Magill rather than Stefanik into his standard-bearer for greater campus restrictions on speech -- even if we think Magill was wrong to begin bending to Stefanik's threats, it's evident that Magill did not originate them. To the contrary, the backlash against Magill -- which Whittington tacitly tried to latch on to -- was and is entirely about her perceived unwillingness to bend sufficiently on protecting free speech. Anyone who was joining the dunk party on Magill was, implicitly or explicitly, endorsing the very unambiguous politics of free speech censorship that Stefanik was explicitly promoting. I can't top Ken White here: "You — and I say this with love — absolute fucking dupes."

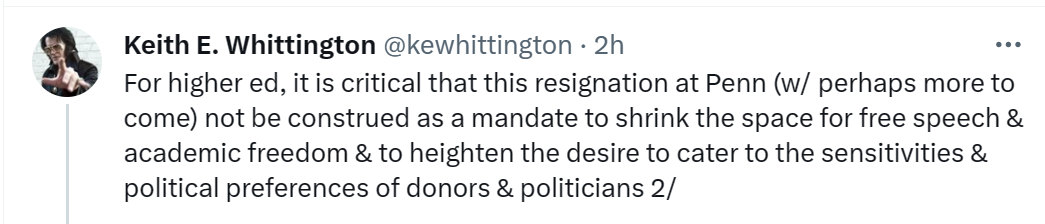

Now that Magill has resigned, here is how Whittington reacted to the news:

It's hard to imagine missing the point by a wider margin than this. Whittington's worried that Magill's resignation will be "construed" as a "mandate to shrink the space for free speech" and to "cater to the sensitivities and political preferences of donors and politicians"? Yeah, no kidding -- it will absolutely be "construed" as doing both of those things because that's exactly what prompted it. The lesson that was meant to be sent and which will be learned is "shrink the space for speech when politicians and donors demand that you do so." There's no ambiguity here; that's the entirety of what happened. Anyone who didn't want that to happen should have come out firing in defense of Magill and in opposition to the roiling censorial mob that Stefanik effectively incited.

Magill felt compelled to resign because she publicly articulated -- in the most hostile room imaginable -- the free speech values that Whittington claims are essential. That's it. And that Whittington still cannot name the actual enemy here -- cannot state clearly that Magill got it right, is being punished for getting it right, and it is rabble-rousing Republican demagogues who showed their whole face in terms of demanding censorship under the guise of protecting Jewish students -- is shameful.

I'm also not feeling especially patient towards some of the other common lines I've heard that try to rationalize why it's okay to blame Magill as having done something wrong. One common response I've seen is to say that the witnesses were poorly prepped for the particular environment of a congressional hearing; with better preparation, they could have avoided the "traps" laid out in front of them. I'm doubtful: I think it is the hubris of very smart people in particular that think they can go into a demagogue's home turf, where they're entirely in control of the proceedings, can control the flow of questioning, can reclaim time whenever they want, and outmaneuver their "traps". It's the same hubris that makes liberals think they can go on Fox News and "outdebate Hannity". No you can't, and it's not because Hannity is some secret genius. It's that he has the home field advantage -- he knows how to play this particular game better than you, precisely because it's a "game" that does not in any way reward intellectual honesty or virtuosity.

A similar argument is that, while the responses of Magill et al may have been formally, legally, correct, they were inappropriate in this context -- their role was not to be lawyers but public advocates for their university, and their sin was misapprehending what was called for from their position in this context. My former colleague at Berkeley Steven Davidoff Solomon, for example, described the university presidents as "prepared to give answers in the court — and not a public forum,” and that was their undoing: their job here is “not to give legal answers, it’s to give the vision of the university."

Once again, I'll cry foul. Yes, there are many situations where a technically correct answer nonetheless can be a bad answer because it skirts some larger truth or is inattentive to important surrounding context, which a good answer would pay heed to. But this argument only works if the problems with the "technically correct" answer are not the facts which make it correct. The people who are mad at Magill are not mad based on something like "yes, maybe it's technically true that there are some circumstances where 'calls to genocide' are protected from formal sanction, but it's more important right now to emphasize how heinous those calls are even if they always be literally punished." The thing they're mad about is the thing that Magill said which was true: there are some circumstances where even 'calls to genocide' -- and we're not even getting into Stefanik's attempt to frame the at the least more ambiguous case of 'intifada' chants as a "call to genocide" -- are protecting from formal punishment. As Howard Wasserman wrote:

Magill, Gay, and Kornbluth did not fail to denounce calls for genocide as antisemitic. No one asked whether calls for genocide or "river to sea" are antisemitic; Stefanik asked whether those statements constitute protected speech and they gave the correct answer of "it depends on context," because it does. In fact, they did at points condemn the message, just without expressing intent to sanction the speech where it remained protected.

Put differently, it's fine to say that in some cases a "technically correct answer" isn't good enough, but only if your proposed alternative is not to demand the speaker be overtly and substantively incorrect.

The last thing I'll say is that I'm not generally interested in point-tallying of the "this is the real cancel culture" variety. Free speech, as I've often said, has mostly fair-weather friends, and no camp has covered itself in glory across the board. What I will say though is that no matter how one tallies the overall scoreboard, this absolutely is an incident where the forces of censorship won and those demanding respect for free speech principles lost. The next time we face an incident where some controversial right-winger comes to campus, it will be a lot harder to persuasively lecture our students that as hateful and heinous as this figure may be, this is the demand of free speech protections etc. etc. etc., because they will have seen in vivid detail just how easily those principles can be forced to bend.

Maybe you think that's a good thing. I still think it isn't. And at the very least, the practical shakeout of who will in practice see their speech censored and who in practice will be able to access administrative protections remains to be seen. I have zero confidence that this will either find a stable and accepted equilibrium or ultimately redound to the benefit of young Jews enduring antisemitism on campus.

5 comments:

I watched the testimony. The question was asked without any attempt to define what a call to genocide was, the clarifications on semantics came after, so I'm unsure why the "Infitada" remark of Mrs. Stefanik is relevant; Magill (and the other two!) failed the question before it got to that point.

The question is only a "trap" question only insofar as it lays the ground for a hard look at the consistency of UPenn's applications of free speech principals. Magill did not make it to the "hard" question because she completely fumbled the softball question.

A "fairweather friend" for free speech is not a friend for free speech, only for free speech they personally agree with. It's hard to look at UPenn's record and say that Magill is a true advocate for free speech rather than a selective one. It would be different if we had the president of University of Chicago out there making this statement, but we did not. And even the President of U of Chicago would do well to include a condemnation of any calls to genocide, of any group.

As one who believes in free speech on Universities I fail to see how pointing out the hypocrisy of those who *selectively* run to free speech principles is failing to defend free speech. Free speech as an ideal only exists with universal application. Nobody deserves applause for allowing speech they support to begin with.

It is not just this one moment either. UPenn as a university has allowed for numerous hostile actions to the point of harassment, and by numerous numerous accounts feels unsafe for current Jewish students. Magill failing to qualify her technically accurate statement with any bit of empathy pushed an existing situation to a boiling point, it did not just create the conditions for her resignation out of thin air.

Eventually you will be forced into a moment where the collective voice must confront your personal experience: there is a loud and clear view among a majority of openly Jewish academics and students, especially at places like UPenn on how unprotected they feel and the double standards they experience. It's great that you have personally only felt somewhat threatened in your community, only having to hide clothing showing signs of overt Jewishness. That doesn't somehow mean that UPenn hasn't failed it's Jewish students and promoted an openly hostile environment, and then displayed little to no empathy at the congressional hearing. That alone can be a sufficient basis for demanding a resignation.

I have never once, in any of my writings, diminished others' accounts of facing antisemitism on campus (or anywhere else). To the contrary, I've consistently urged that we must take these accounts seriously, not view them as ginned up or exaggerated, and that this is true even when I've been fortunate enough not to experience the worst instances directly (and I hope you felt a twinge of shame in leveraging against me my own willingness to be open and vulnerable about how I was experiencing and working through feelings of anxiety about my standing as a Jew, because that's pretty despicable behavior in my view).

What I've always been clear on is that academic freedom is a constraint on remedies -- it doesn't deny problems, it denies the validity of certain solutions to them. There clearly is a problem with respect to antisemitism on many campuses, one that's been exacerbated since 10/7. Stefanik demanded a remedy to that problem that's outside the legitimate authority of the university administration and is beyond hypocritical for anyone with her general views on campus speech. The notion that the backlash towards Magill or her colleagues stems from them failing to adequately perform their obvious view that calls for genocide are condemnable strikes me as absurd, and in any event Stefanik could not have been clearer that this wasn't what she was asking. And the insinuation that any of the three (but especially Kornbluth, who is Jewish) only defended the free speech right to call for genocide against the Jews because it was "speech they support to begin with" is beyond risible.

I disagree. Certainly I don't think you've diminished other's testimony directly in the way you describe -- taking someone's spoken words and actively ignoring them. I think you have implicitly diminished others accounts when you exclusively tie the "resignation" to the testimony, instead of a long-standing series of complaints about antisemitism at UPenn. Donors were walking sideways well before the testimony, articles were written and Magills position was already in question -- that's why she was testifying in the first place, after all!

The testimony was most likely the final straw. This is evidenced by Magill being the first and perhaps only to resign -- MIT has had less public-facing issues, and Harvard reasonably quickly distanced itself from the statements made by its clubs, in a way that communicated disapproval while protecting free speech.

Since you are a well informed commentor on the subject -- no sarcasm intended, truly -- the assumption is that you already knew these circumstances but chose to write an article exlusively treating it as an isolated reaction to the testimony. I apologize if you think I'm using your previous article "despicably", but I find it baffling that one could write an article such as yours, entirely ignoring the prior context of issues at UPenn and with Magill, if you have actually fully appreciated the perspective of those at UPenn. I saw your personal, more positive experience as a potential explanation for why you disincluded this context.

It is only risible that the presidents "support" the speech if you take the least charitable interpretation of that statement. I would not claim that any of the three presidents support the speech in the sense that they agree with the speech -- but I would absolutely would argue that the presidents support the speech with a different set of rules, standards and treatments compared to other hate speech one can see on campus. They do this because they care more -- politically definitely, personally potentially -- about the students espousing the bigotry here compared to your garden variety racist or transphobe and wish to protect them more.

|| "The notion that the backlash towards Magill or her colleagues stems from them failing to || adequately perform their obvious view that calls for genocide are condemnable strikes me || as absurd"

I simply disagree here. From what I've read online, from what I've heard personally across my family and other Jews, the issue very much is with style and not with the substance of a first amendment free speech argument. This being in center-Left Jewish spaces of course, I don't pretend others aren't using this controversy opportunistically.

David,

The error in your analysis and opinion is a misunderstanding of the role of a leader who is not judged on whether they are “right” or “wrong” but on whether they can rise to the occasion in the breach of uncertainty and bring people along. Anyone armed with the legal analysis you provided could have provided her answer - in fact it sounds like more than one president was provided advice by WilmerHale. It’s been unfashionable over the past few decades to think that individuals change the course of history, instead seeing their role as simply a manifestation of their context, but my mind was irrevocably changed when Zelensky single handedly aligned the word to a Ukrainian cause that would have otherwise been defeated by global equivocation and dithering.

If, as you suggest, unimpeded free speech on campus is one of the most important thing for these university presidents to have managed to preserve through these hearings then they failed absolutely. By flailing in their testimony and retracting the following day they in fact not only conceded the point but actually circled around and advocated for the alternative.

Personally, I’m not sure I agree with your perspective on free speech, but that’s up for discussion.

That’s an entirely separate matter from the leadership failure that we witnessed. Leadership does not exist in the arena of “fairness” or certainty. Leadership manifests in its ability to bring people along in the most impossible of situations. We did not see leaders at that hearing - at best we saw poorly advised administrators. As for Macgill she ultimately lacked both integrity (she flipped the next day) and the ability to communicate emotion or compassion. I have a much higher degree of respect for Claudine Gay who expressed remorse and vulnerability the following day by apologizing and expressing her own regret upon personal self-reflection.

We can be guided by principles, but we move forward through leadership in its many forms.

I don’t disagree with free speech absolutism, and indeed have found myself at odds with others in the Jewish community on this topic and protests generally—but there’s an argument I was first seeing on the fringes that seems to be gaining ground. That the “problem” wasn’t necessarily in the technical truth, but in the inconsistent application of free speech ideals and previous censoring (embodied in this economist article https://www.economist.com/united-states/2023/12/12/american-universities-face-a-reckoning-over-academic-freedom).

I don’t have enough insight or understanding here though to figure out if this was just trying to make criticism fit or if there’s something to it.

Post a Comment