Years ago, I wrote a review of a greasy spoon diner I ate at in Oakland called "Pretty Lady". My wife and I had intended to go to a trendy spot called "Brown Sugar" which specialized in contemporary twists on classic American blah blah blah, but the wait was two hours, we were hungry, and so we just found a random restaurant nearby that sounded like it could cook a decent brunch. Pretty Lady was a small place, and its shtick was that the older Asian lady who ran the place would insist on giving every patron a fist bump before she took their order. It was corny and ridiculous, but it made me smile. So we both gave her a fist bump, and then we ordered our fried egg sandwiches, which were perfectly fine but nothing remarkable or especially distinct from any other reasonably competent fried egg I've had.

Anyway, in my review I gave the place four stars -- remarking that while based on food quality alone, it was probably more of a three star, "there is something to be said for a nice hole-in-the-wall that just makes you feel happy from the moment you walk in to the moment you leave." It's possible that the highly accoladed Brown Sugar and its fancy, deep, sophisticated takes on the American brunch, would have been a life-altering experience. And perhaps giving plaudits to a restaurant for a fist-bump and a basic fried egg dish isn't as sophisticated as uncovering the sublime flavors and textures of this year's James Beard award chefs. But I was just happy to be happy, and I thought Pretty Lady deserved to lauded for the simple act of inspiring happiness.

James Greig in Dazed has an article criticizing "adult babies" who, even into their 20s and 30s, enjoy childlike things (Harry Potter, action movies, stuffed animals, etc.). His is not primarily an aesthetic critique, though. He thinks this is politically objectionable. The propensity of adults to consume child-culture -- which covers everything from young adult novels to acting "cute" -- is part of a broader pattern of self-endorsed helplessness; a way for people to come to terms with (rather than challenge) their lack of agency and take pleasure in failing to accept responsibility:

[E]ven if the economy is foisting an extended adolescence on us, we can still choose to assert our dignity and refuse to become “baby adults” or 26-year-old teenagers, helpless and dependent. Make no mistake: the capitalist elites want you to think of yourself as a silly little goose. “From a psychoanalytic perspective, self-infantilisation makes uncannily good sense. It is a kind of identification with one’s own powerlessness, and so gives it a veneer of active choice,” says [philosopher Josh] Cohen.....

What would rejecting this helplessness look like? The right see adulthood as a process of settling down, getting married and having children; in effect, conforming to conventional gender roles and being productive members of the workforce. We obviously don’t have to buy into that, at any age. But we can aspire towards a different form of maturity: looking after ourselves, treating other people with care, being invested in something beyond our own immediate satisfaction. Infantilising yourself can often seem like a plea for diminished responsibility. Most of us will have encountered someone who, when criticised for behaving badly, appeals to their own vulnerability as a way of letting themselves off the hook. No matter what they do or the harm they cause, it’s never fair to criticise them, because there’s always some reason – often framed through therapy jargon or the language of social justice – why it isn’t their fault. Childishness grants them a perpetual innocence; they are constitutionally incapable of being in the wrong.

But we will never make the world better if we act like this. Thinking of yourself as a smol bean baby is a way of tapping out and expecting other people to fight on your behalf.

So here's the thing: the purely political register of this, I endorse -- indeed, I've written regularly about the "infantilization of the American right", in terms that largely echo Grieg's. I absolutely agree that we each have a responsibility to make our own choices in fashions that care about our loved ones and those around us in a respectful fashion; we can't just throw up our hands and act as if we lack agency altogether. But once this political observation proceeds into a cultural critique -- grouchy assertions that kids adults these days are watching the wrong movies/listening to the wrong music/adopting the wrong hobbies -- then I think it is exactly as tendentious and dull as any other moral panic which adopts largely the same tenor.

For starters, one of my bedrock social principles is a strong presumption against begrudging people joy where they find it. There's not so much happiness in the world that we should be too keen on finding reasons to take away people's joy. In this, I think Grieg significantly misdiagnoses why it is that this "childlike" properties hold appeal for many adults. I don't think it is wholly or even predominantly about some fetishization of our own helplessness. I think we're seeing instead an appreciation for uncomplicated joy (and the parallel inability of some progressives to understand why joy-qua-joy is good).

Not everything has to be a grimdark march through serious themes where every halfway decent character ends up brutally murdered by an uncaring universe. Nor, for that matter, does it have to be a complex and shaded exploration of deep philosophical precepts that can generate a dissertation or twelve. Some people do enjoy these things (I often do), and that's great! But other people enjoy other things, and that's fine too. People like Star Wars because it's fun, and it makes them smile, and it doesn't need to do more than that. To be clear: we need to do more than that in the totality of our lives. But that doesn't mean every constituent element of our lives must be a complete balanced diet all in itself. That something "just" sparks joy is absolutely a sufficient reason to like it. Grieg seems to view unmediated joy as the experiential equivalent of empty calories -- we should strive to consume more nutritious fare. I'm inclined to think of joy as an essential vitamin that is an indispensable part of this complete breakfast. How one ingests that vitamin is fundamentally up to us.

The link between the cultural and political critique presumably is that the consuming the "merely" joyful leads to the sort of political infantilization that we both agree is so toxic. But there is no reason why simply "taking joy in things" necessarily leads to the sort of self-infantilization that Grieg critiques. And that's true even if part of its appeal is harkening back to moments of fewer responsibilities and concerns. We go to baseball games in part because it reminds us of bonding moments with our parents, or of how simply meeting your favorite player could be enough to send you into a happy tizzy for a week. Does this nostalgic appeal mean that adults who remain baseball fans are indulging in "a way of learning to love your oppressor"? Is the best way of describing baseball fandom "tak[ing] an acute loss of agency and control and transform[ing] it into a state to be desired and enjoyed"? Or is the small-brain description -- that adults watch baseball because it makes them happy, and that's quite the sufficient justification on its own -- perfectly comprehensive? Some people can write epic narratives that connect baseball to the weighty philosophical themes of life -- some do the same for Star Wars or Harry Potter -- but realistically speaking that's not why most people watch baseball. But good news! That baseball is mostly enjoyed for simpler reasons doesn't mean that baseball fans are progressively losing the ability to take responsibility in other domains! We're perfectly capable of partitioning here.

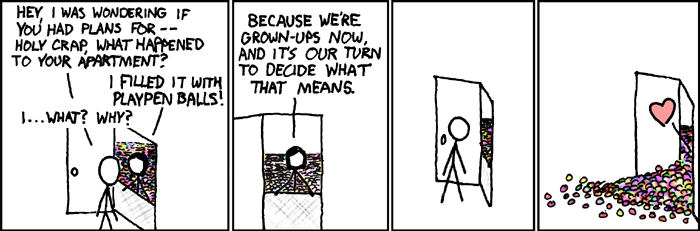

Generational grousing notwithstanding, there is not anything new about most adults regularly enjoying the simpler pleasures (medieval jousts, too, largely demurred from exploring complex and morally shaded themes). Other than adjusting the relevant titles, there is no time period where pompous sniffing about the need to put down Harry Potter and pick up Henry James could not be heard. But the best thing about being adult is our capacity to choose for ourselves what makes us happy -- nobody forces us to play the piano or go to karate practice; we do those things or not because we are in a position to decide what fulfills us. When an adult enjoys Super Mario Brothers, that's not them "choosing" helplessness, it's them choosing joy. Our obligations in a political register extend well beyond this. But in terms of culture, hobbies, and pastimes, Grieg more or less is indignant because people are being happy wrong -- and that's a criticism I just refuse to share.

1 comment:

Yep, while demonstrative vulnerability is definitely bad, and liking YA books too much may be bad sometimes, I dunno, these two don't really have much to do with each other.

Post a Comment