Earlier today, in response to the violent detention of California Senator Alex Padilla for the sin of asking an intemperate question of DHS Secretary Kristi Noem, someone quipped that "We have entered the 'caning of Charles Sumner' stage of historical parallels."

I've been thinking of antebellum precedents myself recently, albeit in response to a different issue: the new propensity of ICE and other federal police agencies to refuse to clearly identify themselves before purporting to make immigration-related arrests, and the corresponding rise in "ICE impersonator" events where criminals and scammers impersonate the agency to victimize vulnerable communities. What we are seeing, again and again, are police actions that to an immediate observer look indistinguishable from a kidnapping, abduction, or carjacking. On the one hand, this indistinguishability heightens Americans' vulnerability to violent crime; on the other hand, the adoption of these thuggish tactics by the police is itself rightly seen as an attempt to leverage terror against the population. Responsible states and cities should not cooperate in this project, and indeed they should take whatever steps they can to resist it.

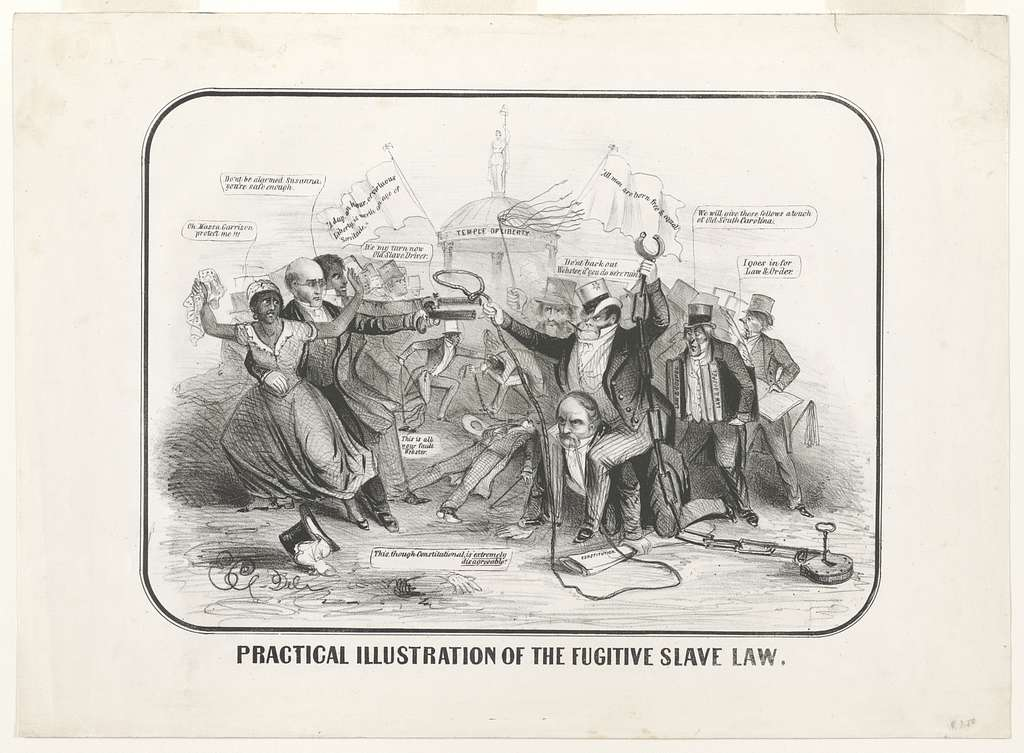

In the antebellum era, many northern states passed "Personal Liberty Laws" to blunt the effect of a different exercise of state-sponsored abductions: the Fugitive Slave Act. My proposal is for a new "Personal Liberty Law", that takes the form of directing how state and local police should respond* if they witness what appears to be a kidnapping, abduction, or the like. In essence, the policy should be as follows:

- Where the police witness what appears to be an abduction, they should assume it is an unlawful abduction and respond accordingly (including with use of appropriate force) unless they have actual knowledge that the detention is occurring under lawful authority (i.e., is an actual police operation).

- "Actual knowledge" can include advance knowledge (in cases of coordination), or conspicuous display of law enforcement identification (such as a badge, or the use of marked police vehicles).

- "Actual knowledge" does not include mere verbal or written declarations (including clothing labels) that the putative kidnapper is a member of any particular police agency, as such declarations are too easily fabricated.