My view on polling Israeli and Palestinian attitudes has always been that we have to take the bitter polls with the sweet and the sweet polls with the bitter. By that I mean we shouldn't contort polls so that they fit our narrative agenda, whether that agenda is a positive view of the parties willingness to compromise or a cynical view that says that one side or the other simply "will never accept" this or that red line.

Under that framework, though, I consider this poll to be quite negative -- and, because of a peculiar methodological decision -- far more negative than it lets on, and in fact may be quite terrifying.

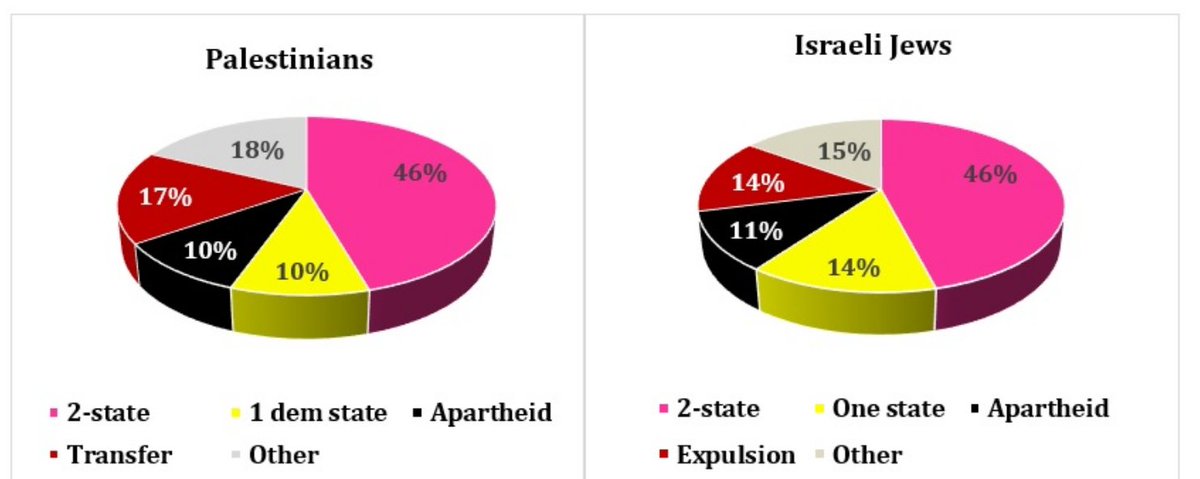

Take a look at this image, from the poll memo:

Just looking at that pie chart, you'd think that the pollsters asked respondents to choose among several potential "solutions" to the conflict: two-state, one-state with equal rights, one-state with only rights for one's own ethnic group ("apartheid"), and one-state where the other ethnic group has been removed (expulsion/transfer). And we'd see that a plurality (albeit a sub-majority plurality) picked the two-state solution, with smaller numbers divided across the other options.

But that's not actually what the pollsters did. Here's their explanation:

What does this mean in practice? Imagine three respondents to the poll. The first, Avi, says he supports a two-state solution and would not endorse any other outcome. The second, Batem, says he prefers a two-state solution over all others, but he would be okay with his ethnic group expelling the other side and ruling the land solo. The third, Chaya, says she prefers a one-state solution where members of the other ethnic group have been expelled, but she would be okay with a two-state solution outcome.The findings show a high level of overlap: in other words, a single respondent often supported more than one of the three alternative options. In the following analysis we sought to identify a “core constituency” for each alternative option: i.e., the greatest number of respondents who would support the most desirable response – for the purposes of this analysis, the two-state solution – even if they support other responses, since policymakers can count on their support for two states. We then quantified the greatest number who supported the second-best option, but who would not support the two-state solution, and so on for the third and least desirable options.To explain how this was done - in the first stage of the analysis, respondents who support a two-state solution are removed from the constituencies that support any of the other alternatives. In a second stage, those who support a one-state solution are removed from the constituencies that support either or both of the remaining two alternatives, apartheid and expulsion. In the final stage, we separate the remaining two groups by removing those who support apartheid from the constituency that supports expulsion.

Not only would all three respondents "count" for the 46% two-state solution figure, but neither Batem nor Chaya would count for the one-state-via-expulsion solution, even though Chaya actually prefers that outcome to a two-state solution. In other words, it's not that 46% of Israelis and Palestinians prefer a two-state solution, it's that 46% of Israelis and Palestinians would accept a two-state solution even though some of them would actually prefer an outcome that's considerably more radical.

By the same token, the poll suggests that 17% of Palestinians and 14% of Israelis would back expelling their counterparts and just keeping the entire land for themselves. But that figure only includes those respondents who are only okay with the expulsion solution. It doesn't include people like Batem, who would back that outcome (albeit as a second-best solution) or even people like Chaya, who prefer that outcome (but are willing to accede to others). The percentage of persons who at least are willing to countenance -- or even prefer -- an expulsion scenario is almost assuredly higher than the figures given.

The pollsters justify this methodological move because they want to encompass the maximum number of people who would back the most "moderate" solution (a two-state). That strikes me as a little dodgy, but fair enough. Still, there's no question that -- insofar as it is being used to reflect the current political temperament amongst Israelis and Palestinians -- it massively overstates practical support for a two-state solution and undersells the support for more radical scenarios.

And what's most frustrating is that the pollsters don't even give us (as far as I see) the underlying figures to let us make apples-to-apples comparisons. I can understand why one wants a measurement of all those who'd at least be willing to support a two-state solution (even if they'd also back other outcomes). But then I'd want to compare that figure to how many persons are at least willing support those other outcomes (the possibility that more persons right now are at least willing to back expulsion -- or, more terrifyingly, prefer the expulsion outcome -- than desire a two-state solution or even a one-democratic-state outcome is left entirely on the table given that data that the pollsters made available).

Ultimately, then, the way this poll is being presented is more than a little shady in order to cast a far rosier picture on Israeli and Palestinian attitudes towards the peace process than I think is warranted. If this isn't quite as bad as those JVP maps (because at least they're explaining their methodology, albeit in a way that makes it clear how they're loading the deck), it's close.