The President of Williams College, Adam Falk, has prevented a student group from hosting a speech by right-wing pundit John Derbyshire. I've actually written once before about a similar flare-up concerning speeches at Williams, concerning the same student group ("Uncomfortable Learning"). But whereas in the last post I argued that the student protesters had struck the right note (protesting the decision to invite the speaker in question, Suzanne Venker, but not demanding that she be "banned"). President Falk's decision is a whole different kettle of fish. It is an outrageous assault on academic freedom, despite the fact that I whole-heartedly agree that Derbyshire's views (and the likely content of his speech) are abhorrent and racist.

The distinction between what happened previously versus in the instant case is simple. As I explained in my Academic Freedom versus Academic Legitimacy essay, academic freedom is a constraint on remedies -- when academics engage in terrible speech, it takes certain responses (banning the speaker, punishing the host group) off the table. It does not, however, preclude arguments that the hosts made a mistake in extending their invitation to someone who ought not be considered a useful contributor to academic discourse; nor does it preclude efforts to convince (not require) the group to reconsider its invitation once extended. These latter moves still need to be justified, of course, and we can fairly object in cases when they seem to be abused. But I don't think they are in of themselves academic freedom violations -- they are academic counterspeech, vital to the project of academic exchange.

By all accounts, it was this latter set of moves that were deployed in the Venker case. And, as Ken White lucidly argues, these arguments would have had considerable purchase against Derbyshire as well (though one significant -- though not necessarily dispositive -- counter-argument is that the African-American President of "Uncomfortable Learning" wanted the opportunity to confront and refute Derbyshire in person). But instead of forceful counterspeech the college administration jumped straight to one of the prohibited remedies. It banned Derbyshire in defiance of the wishes of a student group generally authorized to invite such speakers. There's simply no way to justify such a blunt exercise of administrative coercion against members of the academic community within the constraints of academic freedom.

In reflecting on this case, what jumped to mind was another recent case of a seemingly-terrible, bigoted speaker being invited to present at a northeastern liberal arts college -- Jasbir Puar at Vassar College. Dr. Puar was also invited by duly authorized members of the college community; her hosts (presumably cognizant that she would prove "controversial") even pleaded with the audience not to record her speech (a request, which, incidentally, I find independently outrageous and wholly unwarranted under the circumstances). Her talk was apparently a litany of vicious accusations of Israeli barbarity -- virtually none of which were supported by anything other than raw speculation buttressed by "knowledge" of the innately depraved hearts of Zionist Jewry. She complained that Jews had effectively hijacked the language of victimhood to box off global knowledge of their genocidal tendencies, that Israeli scientists engaged in widespanning medical experiments on Palestinian children to stunt their development and wage genetic warfare against them, and that accordingly boycotting Israel should be part and parcel of a broader strategy of violent attacks against it. The speech appears to be entirely beneath the standards of legitimate academic dialogue. That many academic departments at Vassar considered her to be a worthy contributor to such discourse speaks poorly of their judgment as academics (an assessment which is hardly challenged by the response of one of the inviting professors when challenged as to whether he believed Dr. Puar's allegations: "You prove to me that anything she said wasn’t true." This is an academic talking?).

I do not think Dr. Puar's speech should have been banned. I am perfectly content with responses of the sort I identified above: critiquing the judgment of the invitation while affirming the right of the invitation to be extended. Of course, that's cheap for me to say since her speech already has occurred. And it's possible that the reason the option of an outright ban doesn't appeal to me is simply because I know it's not viable for people in my community; the check President Falk writes is one I know I'm not entitled to cash. I don't think my position is merely a case of sour grapes, but I do think that line of analysis points to a real problem -- what Eugene Volokh has termed "censorship envy". If we are going to censor certain offensive speakers, those outgroups who still are forced to endure speech they find hateful can fairly wonder why they aren't entitled to the protections extended to others. The Jewish student at Vassar can read the goings-on at Williams College and justly ask "why not us? Why should we have to endure what others don't?" It's a fair question. I'm not sure it's an answerable question.

Better, then, to make it a moot question. The fact that we cannot have confidence that college officials or other authorities will distribute the fruits of censorship fairly or equitable is one excellent reason (among many) to deny them that power. Perhaps John Derbyshire should not have been invited to Williams in the first place; perhaps the same can be said about Jasbir Puar. There is much that can be said and perhaps should be said in defense of those points. But academic freedom means respecting the difference between a critique and a prohibition. When that distinction isn't acknowledged, the harm does not just extend to the community deprived of the right to confront those views, or even to to the barred speaker whose views have been deemed out of bounds. It is also felt by the members of all the other communities who know that they will be forced to endure their particular slings and arrows, that hurting them or spewing hate at them is apparently perfectly in bounds. Simply put, Williams College should be just as tolerant (and no further) of John Derbyshire as Vassar College should have been towards Jasbir Puar.

Saturday, February 20, 2016

Thursday, February 18, 2016

The Issue is Mizrahi Power

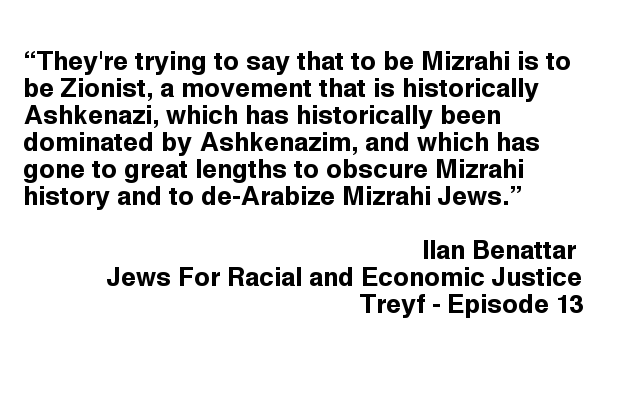

The article Analucia Lopezrevoredo and I wrote on the general failure of intersectional analysis to account for Mizrahi Jewish experience (and, more generally, how Mizrahi Jewish experience is erased in broader discourse about Jews -- regardless of whether the speaker falls on the ideological spectrum) has been featured on the Treyf podcast. They brought on llan Benattar from Jews for Racial and Economic Justice’s Mizrahi caucus to comment; he was ... not a fan. The podcast hosts themselves alluded to finding many of our points interesting, but never really got to say which ones -- one gets the sense, though, that their position is that "the article raised a lot of good points right up until the parts where it implicated us in the problem."

In any event, speaking for myself and not Analucia or JIMENA (who are capable of correcting the misapprehensions Benattar has about JIMENA's mission), I found that Benattar's comments were an excellent encapsulation of our core thesis regarding Mizrahi Jewish inclusion (or lack thereof) in broader patterns of discourse.

Let's put two excerpts side by side. Here is how Benattar charaacterizes the core argument of our article, which he terms a case of "Mizrahi-washing":

The reason we link this up to certain practices in anti-Zionist circles isn't because "to be Mizrahi is to be Zionist", it's simply because as a matter of raw numerical fact many are, and "irrespective of whether those terms are Zionist" cuts both ways. If one excises the Zionist part of the Mizrahi community from the part one is willing to talk to, one is left with a lot fewer Mizrahim. That is no doubt to the benefit of Ilan Benattar, since it means a lot more people will be talking to him. But it is not a viable nor a progressive proposition for engaging across difference; it inscribes the very sort of exclusion we critique.*

Indeed, I think we need to interrogate the move being made here more closely. It is highly reminiscent of Herman Cain's plantation politics: Most Blacks are being duped and deceived by the Democratic Party which wants to keep them "on the plantation," their condition is used as a tool to support politics "we" (those like Cain) know are bad, but a few Blacks, like Cain, "can think for themselves" and are the ones you should listen to. And likewise, Benattar casts contemporary Mizrahi politics as being obscured from itself, the product of a Zionist-Ashkenazi effort to make it in its own image for its own ends, such that it is okay to generally ignore Mizrahi Jews (who largely remain on the Zionist plantation) in favor of the few, like him, who see past the ruse and can tell you what's what.

Now here I want to be very careful about the point being made. It is not that Jews (Mizrahi or otherwise) are not entitled to critique or dissent from the prevailing orthodoxies in the community. I do not believe that Ilan Benattar or Herman Cain (or Ben Carson or Clarence Thomas or Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz) have any particular obligation to adopt the political posture of their broader community. I have always firmly taken the stand that there is no legitimate politics (based on solidarity or anything else) that writes such dissent out; and that means (among other things) that it is flatly wrong to claim that Jewish anti-Zionists have forfeited their Jewishness by virtue of their position. From my personal vantage point, such a stance would make me a terrible Zionist -- I view Zionism as about Jewish self-determination, and that includes the right of a Jewish self to determine that Zionism is incompatible with their assessment of the Jewish condition or Jewish obligations. One can argue against the positions on their merits; but the fact of adopting the positions doesn't mean the speaker "isn't Jewish" or is a "self-hating Jew" or whatnot (for the same reasons I object to referring to Cruz or Thomas as race traitors or Uncle Toms or what have you). Jews should have the same right as anyone else to come to positions that you or I think are wrong.

So the problem isn't the critique itself, that's fair game. The problem rather is in the final step -- the proffer that one can justly ignore most members of the outgroup and instead only speak to the dissident wing. That silencing -- really tokenizing -- move is what's objectionable; the forwarding of oneself as a substitute for engagement with the broader community constructed as defective and unworthy of deliberative inclusion. When outgroups (whether we're talking about Jews generally, or Mizrahi Jews specifically, or Blacks, or Latinos, or Palestinians for that matter) say things that are hard to hear or which raise difficult critiques of passionately-held positions, the right move is not to race off to find your friend who agrees with you and be assured that everything's alright. One need not assent, but one should at least listen and think. And so here I will cop to at least one of the many motives that Benattar ascribes to Analucia and myself: We do need to engage with Mizrahi perspectives in Israel, even when they seem quite distant from our own ethnic, political, or cultural priors. Why? Because that's what one does when trying to ethically encounter difference -- particularly difference that is paired with historical patterns of marginalization.

In terms of substantive responses to our article, I think that covers it. But I did also want to make a note of one of the particular rhetorical stylings that was deployed. Throughout his segment, Benattar accused Analucia and I of "co-opting" the language of intersectionality for our own supposedly right-wing ambitions. He used this word so many times I think he must have hired Marco Rubio's speech coach. And on one level, I find this amusing: I've sometimes remarked that intersectionality brings out my inner hipster -- I was reading it way before it was cool (before Benattar even got to college, in fact) -- so who's really appropriating what here?

But the bigger point is, once again, about exclusion. The language of "co-option", obviously, is intricately connecting to the language of standing -- who is authorized to use terms like "intersectionality" and who is trespassing? We already knew, of course, that Jews generally have no standing to utilize such terms on our own behalf, we now know the same is true of non-Ashkenazi Jews specifically (at least when they do so in ways that are not ideologically amenable to particular elements of the left). Our alleged deficiency is that we are insufficiently "progressive"; left unsaid is who established the metric of "progressive" and who installed Benattar as its arbiter. Why should Analucia or myself cede him, or anyone else, that authority? Why is it just accepted that Jewish entry into progressive spaces is always on a probationary basis?

One can see a very particular sort of anti-Semitic exclusion operating here: Jews are not equal members of political communities (progressive or otherwise) we inhabit; we are members to the extent that others permit us to be; which typically manifests as membership to the extent that we affirm the understandings of the dominant groups. Hence, when we level what we take to be a progressive critique at a progressive discourse surrounding Jews, the fact of our dissent is itself sufficient to exile us from the relevant interpretative community. We are not entitled to stake independent claims on progressive concepts when doing so conflicts with how the "real" progressives, the people empowered to govern the borders of "progressive", conceptualize the understanding of "progressive." It's the same damn sin again, we are entitled to partake in discourse "only as far as [we] support someone else’s narrative."

The issue, as Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz wrote so long ago, is power. Who has it, who wants it. In both the substantive and rhetorical formulations, one can see how Benattar's goal is to delegitimize wide swaths of deliberative contributions from progressive consideration and concentrate progressive discursive power in the hands of people like himself. There is no space for an internal progressive critique by Jews of progressive discourse, because once it emerges it ceases being progressive (now right-wing trolling). There is no space for a Mizrahi critique of anti-Zionist practices because once it emerges it ceases being Mizrahi (now Ashkenazi false consciousness). Hence how Analucia and JIMENA can each be dismissed here as co-opters and appropriators -- what credential exactly are they missing such that their deployment of the term intersectionality is inauthentic? For other readers, of course, the problem is inverted -- there is no space for a Mizrahi critique of Jewish Zionist practices because once it emerges it ceases to be Jewish (what, exactly, are they missing?). All of this is the same politics -- just swapping out whose ox is gored. Progressivism, as I understand it (and we already know how much that's worth) is about breaking down such patterns of power and domination. Progressivism, as many others understand it, seems to be more about reshuffling the deck.

The issue is power -- who has it, who wants it. I do not think that Mizrahi Jews, or any Jews, need to be Zionist, I do not think that it is my place to tell Mizrahi Jews what to be. I think that Mizrahi Jews, like all Jews, should be decide for themselves how they conceptualize their condition and their situation; as it happens, many have decided that Zionism fits, some have come to a contrary conclusion. And then I think that other people should be willing to listen and engage with their reckoning, regardless of whether it coheres to the narratives we began with or not.

* Here Benattar accuses us of ignoring the BDS movement's long-stated principle that it targets "institutions, not individuals". The reason I ignore it is that it is impossible to credit. First, I'm dubious that the alleged principle is even a coherent one, as if in multilayered and stratified societies any of us come in as atomized individualized disconnected from surrounding social, cultural, or academic institutions (such a libertarian way of looking at human experience is particularly difficult to swallow in a discussion of intersectionality, which is quite concerned with how we are bound up in a multitude of overlapping identity affiliations that cannot be disaggregated from our core "individual" selves). And second, even if the principle could be expressed coherently it has been breached so often in practice that I can't view it as anything other than rhetorical. There is no serious likelihood that the BDS movement will, in fact, engage with the Israeli Mizrahi community as currently constituted regardless of whether they try to speak "individually" or "institutionally"; more likely (as in the "A Wider Bridge" fiasco -- an organization which, incidentally, has been far better than most about incorporating Mizrahi voices) any efforts to bring such "individual" voices to the fore will be deemed "institutionally" suspect (Benattar even throws out the term "Mizrahi-washing") and thus subject to boycott.

In any event, speaking for myself and not Analucia or JIMENA (who are capable of correcting the misapprehensions Benattar has about JIMENA's mission), I found that Benattar's comments were an excellent encapsulation of our core thesis regarding Mizrahi Jewish inclusion (or lack thereof) in broader patterns of discourse.

Let's put two excerpts side by side. Here is how Benattar charaacterizes the core argument of our article, which he terms a case of "Mizrahi-washing":

And here is the part of our article that is most directly germane:

When asked to speak at certain Zionist functions, many Jewish refugees from the Middle East and North Africa are asked to focus on the mistreatment they experienced under Arab rule—not the ways in which they successfully coexisted with Muslims, or the serious discrimination they have faced in Israeli society after arriving in the Promised Land. In anti-Zionist circles the situation inverts: the hosts are delighted to hear tales of Israeli malfeasance but are deeply hostile if the topic turns to the oppression and expulsion of Jews from Arab countries or if the Jews proclaim a proud connection to Israel. Either way, non-Ashkenazi Jews are engaged with only as far as they support someone else’s narrative. Once they seek to speak in their own voice, their putative allies disappear.Not only are we perfectly cognizant of the manner in which Ashkenazim have historically been dominant in Zionist circles and have sought to deemphasize the interconnection many Mizrahi Jews have had with Arab history, particularly when they clash with Zionist narratives, we lead with it. Our sin is nothing more than the concurrent observation that the same is true of the anti-Zionist movement: also historically Ashkenazi dominated (at least in its Jewish manifestation), also quite prone to deemphasizing aspects of Mizrahi identity when they conflict with anti-Zionist shibboleths. The sins are identical: "non-Ashkenazi Jews are engaged with only as far as they support someone else’s narrative." None of this is to say that there have not been significant Zionist and anti-Zionist Mizrahi voices, none of this is to say that "to be Mizrahi is to be Zionist" (or not). To frame the question in this way misses the point entirely. We are quite clear that the crucial obligation for non-Mizrahim is to confront the community as it is, on its terms, irrespective of whether those terms are Zionist. It's not us that are seeking to essentialize Mizrahim into one mode of being vis-a-vis Zionism.

The reason we link this up to certain practices in anti-Zionist circles isn't because "to be Mizrahi is to be Zionist", it's simply because as a matter of raw numerical fact many are, and "irrespective of whether those terms are Zionist" cuts both ways. If one excises the Zionist part of the Mizrahi community from the part one is willing to talk to, one is left with a lot fewer Mizrahim. That is no doubt to the benefit of Ilan Benattar, since it means a lot more people will be talking to him. But it is not a viable nor a progressive proposition for engaging across difference; it inscribes the very sort of exclusion we critique.*

Indeed, I think we need to interrogate the move being made here more closely. It is highly reminiscent of Herman Cain's plantation politics: Most Blacks are being duped and deceived by the Democratic Party which wants to keep them "on the plantation," their condition is used as a tool to support politics "we" (those like Cain) know are bad, but a few Blacks, like Cain, "can think for themselves" and are the ones you should listen to. And likewise, Benattar casts contemporary Mizrahi politics as being obscured from itself, the product of a Zionist-Ashkenazi effort to make it in its own image for its own ends, such that it is okay to generally ignore Mizrahi Jews (who largely remain on the Zionist plantation) in favor of the few, like him, who see past the ruse and can tell you what's what.

Now here I want to be very careful about the point being made. It is not that Jews (Mizrahi or otherwise) are not entitled to critique or dissent from the prevailing orthodoxies in the community. I do not believe that Ilan Benattar or Herman Cain (or Ben Carson or Clarence Thomas or Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz) have any particular obligation to adopt the political posture of their broader community. I have always firmly taken the stand that there is no legitimate politics (based on solidarity or anything else) that writes such dissent out; and that means (among other things) that it is flatly wrong to claim that Jewish anti-Zionists have forfeited their Jewishness by virtue of their position. From my personal vantage point, such a stance would make me a terrible Zionist -- I view Zionism as about Jewish self-determination, and that includes the right of a Jewish self to determine that Zionism is incompatible with their assessment of the Jewish condition or Jewish obligations. One can argue against the positions on their merits; but the fact of adopting the positions doesn't mean the speaker "isn't Jewish" or is a "self-hating Jew" or whatnot (for the same reasons I object to referring to Cruz or Thomas as race traitors or Uncle Toms or what have you). Jews should have the same right as anyone else to come to positions that you or I think are wrong.

So the problem isn't the critique itself, that's fair game. The problem rather is in the final step -- the proffer that one can justly ignore most members of the outgroup and instead only speak to the dissident wing. That silencing -- really tokenizing -- move is what's objectionable; the forwarding of oneself as a substitute for engagement with the broader community constructed as defective and unworthy of deliberative inclusion. When outgroups (whether we're talking about Jews generally, or Mizrahi Jews specifically, or Blacks, or Latinos, or Palestinians for that matter) say things that are hard to hear or which raise difficult critiques of passionately-held positions, the right move is not to race off to find your friend who agrees with you and be assured that everything's alright. One need not assent, but one should at least listen and think. And so here I will cop to at least one of the many motives that Benattar ascribes to Analucia and myself: We do need to engage with Mizrahi perspectives in Israel, even when they seem quite distant from our own ethnic, political, or cultural priors. Why? Because that's what one does when trying to ethically encounter difference -- particularly difference that is paired with historical patterns of marginalization.

In terms of substantive responses to our article, I think that covers it. But I did also want to make a note of one of the particular rhetorical stylings that was deployed. Throughout his segment, Benattar accused Analucia and I of "co-opting" the language of intersectionality for our own supposedly right-wing ambitions. He used this word so many times I think he must have hired Marco Rubio's speech coach. And on one level, I find this amusing: I've sometimes remarked that intersectionality brings out my inner hipster -- I was reading it way before it was cool (before Benattar even got to college, in fact) -- so who's really appropriating what here?

But the bigger point is, once again, about exclusion. The language of "co-option", obviously, is intricately connecting to the language of standing -- who is authorized to use terms like "intersectionality" and who is trespassing? We already knew, of course, that Jews generally have no standing to utilize such terms on our own behalf, we now know the same is true of non-Ashkenazi Jews specifically (at least when they do so in ways that are not ideologically amenable to particular elements of the left). Our alleged deficiency is that we are insufficiently "progressive"; left unsaid is who established the metric of "progressive" and who installed Benattar as its arbiter. Why should Analucia or myself cede him, or anyone else, that authority? Why is it just accepted that Jewish entry into progressive spaces is always on a probationary basis?

One can see a very particular sort of anti-Semitic exclusion operating here: Jews are not equal members of political communities (progressive or otherwise) we inhabit; we are members to the extent that others permit us to be; which typically manifests as membership to the extent that we affirm the understandings of the dominant groups. Hence, when we level what we take to be a progressive critique at a progressive discourse surrounding Jews, the fact of our dissent is itself sufficient to exile us from the relevant interpretative community. We are not entitled to stake independent claims on progressive concepts when doing so conflicts with how the "real" progressives, the people empowered to govern the borders of "progressive", conceptualize the understanding of "progressive." It's the same damn sin again, we are entitled to partake in discourse "only as far as [we] support someone else’s narrative."

The issue, as Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz wrote so long ago, is power. Who has it, who wants it. In both the substantive and rhetorical formulations, one can see how Benattar's goal is to delegitimize wide swaths of deliberative contributions from progressive consideration and concentrate progressive discursive power in the hands of people like himself. There is no space for an internal progressive critique by Jews of progressive discourse, because once it emerges it ceases being progressive (now right-wing trolling). There is no space for a Mizrahi critique of anti-Zionist practices because once it emerges it ceases being Mizrahi (now Ashkenazi false consciousness). Hence how Analucia and JIMENA can each be dismissed here as co-opters and appropriators -- what credential exactly are they missing such that their deployment of the term intersectionality is inauthentic? For other readers, of course, the problem is inverted -- there is no space for a Mizrahi critique of Jewish Zionist practices because once it emerges it ceases to be Jewish (what, exactly, are they missing?). All of this is the same politics -- just swapping out whose ox is gored. Progressivism, as I understand it (and we already know how much that's worth) is about breaking down such patterns of power and domination. Progressivism, as many others understand it, seems to be more about reshuffling the deck.

The issue is power -- who has it, who wants it. I do not think that Mizrahi Jews, or any Jews, need to be Zionist, I do not think that it is my place to tell Mizrahi Jews what to be. I think that Mizrahi Jews, like all Jews, should be decide for themselves how they conceptualize their condition and their situation; as it happens, many have decided that Zionism fits, some have come to a contrary conclusion. And then I think that other people should be willing to listen and engage with their reckoning, regardless of whether it coheres to the narratives we began with or not.

* Here Benattar accuses us of ignoring the BDS movement's long-stated principle that it targets "institutions, not individuals". The reason I ignore it is that it is impossible to credit. First, I'm dubious that the alleged principle is even a coherent one, as if in multilayered and stratified societies any of us come in as atomized individualized disconnected from surrounding social, cultural, or academic institutions (such a libertarian way of looking at human experience is particularly difficult to swallow in a discussion of intersectionality, which is quite concerned with how we are bound up in a multitude of overlapping identity affiliations that cannot be disaggregated from our core "individual" selves). And second, even if the principle could be expressed coherently it has been breached so often in practice that I can't view it as anything other than rhetorical. There is no serious likelihood that the BDS movement will, in fact, engage with the Israeli Mizrahi community as currently constituted regardless of whether they try to speak "individually" or "institutionally"; more likely (as in the "A Wider Bridge" fiasco -- an organization which, incidentally, has been far better than most about incorporating Mizrahi voices) any efforts to bring such "individual" voices to the fore will be deemed "institutionally" suspect (Benattar even throws out the term "Mizrahi-washing") and thus subject to boycott.

Labels:

anti-semitism,

Jews,

Middle East,

Mizrahi Jews

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

Anti-Semitism at the Oxford Labour Club

The (now-former) co-chair of the Oxford University Labour Club announced his resignation, citing rampant anti-Semitism within the organization:

"Despite its avowed commitment to liberation, the attitudes of certain members of the club towards certain disadvantaged groups was becoming poisonous," [Alex] Chalmers wrote.Oxford's Jewish Society (JSoc) released the following statement of its own:

"Whether it be members of the Executive throwing around the term 'Zio' (a term for Jews usually confined to websites run by the Ku Klux Klan) with casual abandon, senior members of the club expressing their 'solidarity' with Hamas and explicitly defending their tactics of indiscriminately murdering civilians, or a former Co-Chair claiming that 'most accusations of antisemitism are just the Zionists crying wolf,’ a large proportion of both OULC and the student left in Oxford more generally have some kind of problem with Jews," Chalmers continued.

Oxford University Jewish Society is saddened by the anti-semitic reports coming out of Oxford University Labour Club, and stands fully in support of Alex Chalmers' decision to resign.

We are, however, unsurprised by this news. It is not the first time that Oxford JSoc has had to deal with anti-semitic incidents within the student left and it will not be the last. It is a significant and worrying issue and one that on many occasions, Jewish students have felt that they are fighting alone. We are grateful that Alex Chalmers has made the statement that he did and has brought the issue of anti-semitism to the fore in a way that Jewish students have so far been denied.

Oxford JSoc strongly rejects any accusation that Jewish students are inventing claims of anti-semitism to discredit Palestinian solidarity politics. This is a repeated trope that has been used to silence Jewish students and it will carry weight no longer. When anti-semitism intersects with Palestinian solidarity politics, it is not the job of Jewish students to be quiet, but the job of Palestinian solidarity activists to rid their movement of anti-Jewish prejudice.

Many of Oxford’s Jewish students who hold progressive views have long felt excluded from left-wing political spaces. Jewish students who raised the issue of anti-semitism at the OULC meeting were laughed at and mocked. It is high time that this issue is confronted. We hope Alex’s resignation triggers a broader awakening amongst student political movements, and that anti-semitism, particularly on the student left, is finally taken seriously.That third paragraph is critical, and needs to be repeated over and over again. Jews have been too deferential to the Livingstone Formulation for too long, and it's high time it stopped carrying weight. Our sense of alienation and maltreatment is entitled to the same respect and concern as any other outgroup; casting it as a bad faith ploy is no less reactionary than when any other group is claimed to be "playing a card".

Monday, February 15, 2016

Jane Kelly For SCOTUS?

I've been hearing murmurings that Eighth Circuit Judge Jane Kelly might be the President's SCOTUS nominee. And there are a lot of dimensions along which that makes a lot of sense.

I've never actually met Judge Kelly, but I'm quite familiar with her. She arrived on the Eighth Circuit in 2013 midway through my clerkship with Judge Murphy, finally ending the latter's streak as the only woman ever to serve on that court nearly 20 years after she was first appointed. Kelly's confirmation was unusually easy in this day and age -- a 96-0 vote taken three months after her nomination -- apparently because she is very well liked by Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley. The Republican chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee is no small ally for a prospective Obama nominee to have. And it would be difficult for Republicans to justify blocking a nominee they quickly and unanimously confirmed to the Eighth Circuit barely three years ago.

Beyond the purely tactical concerns, Judge Kelly is an interesting choice for another reason: Prior to her elevation to the bench, she was a career public defender, working in the Northern District of Iowa from 1994 to 2013. That background is extraordinarily uncommon on the federal bench, and I believe entirely unheard of on the Supreme Court. Her nomination would certainly have particular resonance in the current political moment where overstretches of the police state have been a central issue occupying progressive activist thought.

Now normally, what that background giveth, it also taketh away -- it is very easy to caricature a federal public defender as "soft on crime" (pluck out the most gruesome murderer she ever defended and ask why she wanted to keep him on the streets). But -- and not to get too macabre -- Judge Kelly has a personal story here too that helps insulate her from that particular angle of attack: she was beaten unconscious and left for dead in an unsolved 2004 assault. She is far more intimately familiar with the ravages of violent crime than nearly any other high-level government official in the United States.

Of course, if Judge Kelly were nominated and confirmed, that would restore Judge Murphy as the sole woman on the Eighth Circuit (and -- perhaps even more amazingly -- would also leave her the only active Democratic-appointee on it). But I get the sense she wouldn't mind. Judge Kelly would certainly put a lot of pressure on Senator Grassley and the wing of the GOP Senate that still isn't 100% comfortable with government-via-tantrum. And beyond that, I don't think she'd make a half-bad Justice either.

UPDATE: Speaking of Grassley, he's stepped back from the edge a bit, saying he won't decide whether to hold hearings on President Obama's nominee until the nomination is announced. Admittedly, other quotes from the same interview are less promising. But if this is a slight step towards rapprochement, a Kelly nomination could be just the way for Obama to respond in kind.

(I'm going to just say I'm predicting a Kelly nomination now. It's a bit of a dark horse pick, but I'm undefeated so far in Obama SCOTUS predictions so why not roll the dice a bit?).

I've never actually met Judge Kelly, but I'm quite familiar with her. She arrived on the Eighth Circuit in 2013 midway through my clerkship with Judge Murphy, finally ending the latter's streak as the only woman ever to serve on that court nearly 20 years after she was first appointed. Kelly's confirmation was unusually easy in this day and age -- a 96-0 vote taken three months after her nomination -- apparently because she is very well liked by Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley. The Republican chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee is no small ally for a prospective Obama nominee to have. And it would be difficult for Republicans to justify blocking a nominee they quickly and unanimously confirmed to the Eighth Circuit barely three years ago.

Beyond the purely tactical concerns, Judge Kelly is an interesting choice for another reason: Prior to her elevation to the bench, she was a career public defender, working in the Northern District of Iowa from 1994 to 2013. That background is extraordinarily uncommon on the federal bench, and I believe entirely unheard of on the Supreme Court. Her nomination would certainly have particular resonance in the current political moment where overstretches of the police state have been a central issue occupying progressive activist thought.

Now normally, what that background giveth, it also taketh away -- it is very easy to caricature a federal public defender as "soft on crime" (pluck out the most gruesome murderer she ever defended and ask why she wanted to keep him on the streets). But -- and not to get too macabre -- Judge Kelly has a personal story here too that helps insulate her from that particular angle of attack: she was beaten unconscious and left for dead in an unsolved 2004 assault. She is far more intimately familiar with the ravages of violent crime than nearly any other high-level government official in the United States.

Of course, if Judge Kelly were nominated and confirmed, that would restore Judge Murphy as the sole woman on the Eighth Circuit (and -- perhaps even more amazingly -- would also leave her the only active Democratic-appointee on it). But I get the sense she wouldn't mind. Judge Kelly would certainly put a lot of pressure on Senator Grassley and the wing of the GOP Senate that still isn't 100% comfortable with government-via-tantrum. And beyond that, I don't think she'd make a half-bad Justice either.

UPDATE: Speaking of Grassley, he's stepped back from the edge a bit, saying he won't decide whether to hold hearings on President Obama's nominee until the nomination is announced. Admittedly, other quotes from the same interview are less promising. But if this is a slight step towards rapprochement, a Kelly nomination could be just the way for Obama to respond in kind.

(I'm going to just say I'm predicting a Kelly nomination now. It's a bit of a dark horse pick, but I'm undefeated so far in Obama SCOTUS predictions so why not roll the dice a bit?).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)