- I couldn't think of any particular reason to oppose it; and

- Supporting gay marriage was, descriptively, a fringe position that was outside the bounds of mainstream political discourse.

Being 14 years old or so, the second point was enough to at least keep me quiet on the matter. Who wants to be a non-serious outsider?

A few years later, of course, things had changed. Well before Obergefell, gay marriage crossed over into being at least a plausible political position -- one that people in my circle could openly avow without embarrassment or fears of being shunned or excluded. And once that happened, reason #1 was left alone and asserted itself without trouble. I never looked back.

I suspect that many people experienced an evolution like mine. Most people are reticent to radically break from their social neighbors -- not necessarily something to be proud of, to be sure, but descriptively accurate. And it's not simple bandwagoning -- the privately held position is genuine, but it just doesn't manifest until we are confident that expressing the position won't cause us to be expelled from our relevant social groups. Of course, the "relevant social group" would differ from person to person. The sorts of signals which demonstrate that a position is no longer fringe in legal academic circles, differ from those which provide the same message to judicial elites, versus to Democrats, versus to Mississippians. Nonetheless, I think a story of this sort accounts for the astonishingly rapid shift in attitudes about gay marriage over the course of only a few years. From 2001 to 2015, support for gay marriage gained a whopping 38 points (from net-negative 22% to net-positive 16%).

One way of formalizing the story I just told is through the lens of pluralistic ignorance. Pluralistic ignorance exists when people may personally reject a given social norm but sharply overestimate the degree to which their fellows support it. So I personally have no problem with gay marriage, but I assume all my neighbors do (and many of them, privately, are thinking the exact same thing). Since people frequently won't articulate opinions they believe are unpopular within their peer group, this can result in the maintenance of archaic social norms even when many people privately would be fine with abandoning them. It also explains why, under the right circumstances, these norms can disintegrate with astounding rapidity. If some peer members do articulate the supposedly taboo "dissident" opinion and nothing bad happens to them, then it opens the door for everyone else to articulate their own true views.

The example I just used is a happy one -- people rapidly changing their minds to favor gay equality. But pluralistic ignorance does not always dam up progressive social reform. A few months ago, I told a story about racism and the Donald Trump campaign that moves to a very similar beat. I hypothesized that a significant swath of Americans had learned to cover up their racial prejudices under the belief that such views would be seen as unacceptable by their fellows. If they expressed them, they would be ostracized and shunned (perhaps by the ever-mythic "PC police"). And then Donald Trump came along and said all of the outrageous, biased, bigoted, racist things these covert racists had been yearning to yell out themselves.

...And nothing happened. Sure, the media fulminated and Trump's opponents cried foul. But it didn't sink Trump's campaign. If anything, it strengthened it. There certainly was no social banishment, no exile to the fringe corners of outcasts and misfits. Instead, the racists found that there were in fact plenty of people who believed the same things they did, that they held a non-trivial swath of public opinion and political power. And once they realized that, the dam broke. All that suppressed racial ressentiment came pouring out in full force and fury, shocking even conservative political pundits. The outlook which had been the joke, the province of fringe lunatics, suddenly was looking like the dominant force in one half of America's two-party system.

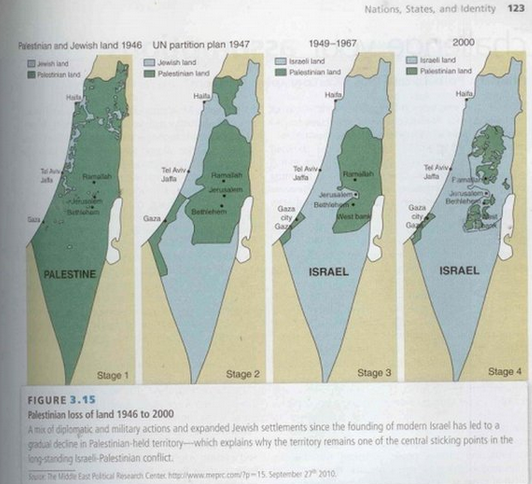

This pluralistic ignorance story may apply to views on Israel as well. CNN may have overstated things when it declared that "Bernie Sanders Smashed the Israel Status Quo" -- as J.J. Goldberg and Gershom Gorenberg, among others, has pointedly observed, Bernie lies well within a perfectly recognizable strand of contemporary Israel advocacy that has never been troubled by "criticism of Israel" -- but it was hardly entirely wrong either. In academia, the rise of BDS is perhaps a more clear demonstration of the effect. It's less about whether they win or lose, and more about signaling that positions on Israel hitherto regarding as extreme -- challenging its entire existence, declaring the entire Jewish national project to be a form of illicit domination -- are not in fact fringe ones. Anti-Israel activists like to tell a story about how marginalized and muzzled they are, but in many ways they're experiencing the exact opposite -- they can give their blood libel spiel, spout vicious anti-Semitic slurs, even falsify their data, and they'll still have a loud and raucous band of petition-signers ready to have their backs. Just like the formerly covert racist who attends the Trump rally and discovers that he was not, in fact, exiled to become a complete social outcast, the extreme anti-Israel activists have discovered that there is a place for them in mainstream discourse. And that means that all those who were privately outraged that Jews dared have a state to call their own but assumed such thoughts could not be expressed aloud, now have an accepted public outlet for their fury. Ressentiment rides again.

And what of outright anti-Semitism (which, of course, is distinct from hostile attitudes towards Israel but certainly often comes clothed in anti-Israel garb)? While it is standard-issue nowadays to claim that anti-Semitism is over, that Jews have officially won the anti-discrimination game (look at how well we poll!), there is a potential pluralistic ignorance story to be told here as well. If it is widely assumed that it's "not okay" to hate on the Jews, then most people will not admit to doing so. The question is -- what happens if that consensus is broken? If people express anti-Semitic attitudes, is it viewed as unacceptable? Does it shatter their reputation, the way it is so often assumed to do?

Right now, things stand on uncertain ground. A Stanford student leader says it is important to consider whether Jews really do control the banks and media -- but then again, the reaction by his peers was clear and unambiguous (yet, on the other other hand, will there be any reputation lost for the Stanford professor who wants people to get their news from blood libel advocates?). An Oberlin professor posts a slew of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, and the university administration seemed barely able to muster up a response. But then a majority of Oberlin faculty did sign a letter denouncing them. But a significant minority of the faculty pointedly refused to do so, expressing "outrage[] at the irresponsible hostility drummed up against [Karega] as a scapegoated target." And round and round we go.

Pluralistic ignorance is by its nature a very speculative story to tell (at least projecting forward). And it depends on the peer groups one inhabits -- liberal college activist groups or conservative white nationalist communities are not every community (and it's worth noting that even in those communities pluralistic ignorance might manifest in its own way -- for example, progressive college students might feel compelled to sign on to far harsher condemnations of Israel than they personally feel are warranted because they jointly assume that is the norm position among progressive college students). But it is one reason I don't think one can rely on the stability of a "norm" against racism or anti-Semitism. It's possible it reflects genuine egalitarian commitments, free from misconceived notions about the attitudes of their peers. But it's possible it doesn't. And if not, the constructed edifice of respect and equality can all come tumbling down very, very quickly.