In the wake of

303 Creative,

I argued that one consequence of the Supreme Court's decision would be to supercharge "cancel culture". In a world where a business' decision to serve (or not) a customer is "free speech", then it must be the case that a customer's decision not to patronize a business (and to urge others to follow) is free speech in turn. Indeed, if we follow the metaphor along, "cancel culture" is exactly what the Supreme Court recommends as a remedy for Lorie Smith's homophobic speech, in lieu of enforcement of the anti-discrimination laws the Court struck down. "More speech, not enforced silence" indeed. And what more speech could we ask for than a concerted, express(ive) attempt to boycott her business, to send the message that these views are awful and intolerable and should wither on the vine of the "marketplace of ideas"?

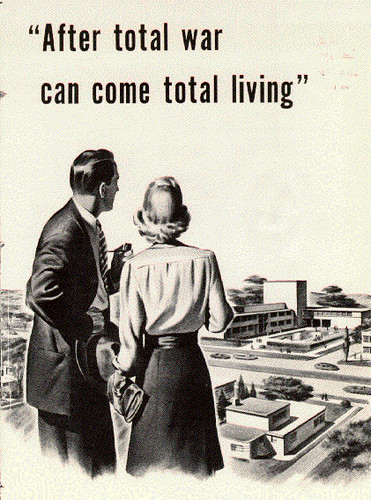

In this way, 303 Creative really did greatly proliferate freedom of speech. But it isn't the freest speech we can imagine. In a Hobbesian sense, the freest free speech regime is one of pure anarchy: anyone can say anything, and anything anyone can persuade anyone else to do is fair game. Hobbes' freedom was the pure war of all against all, with no constraining rules or boundaries whatsoever. Every domain is a legitimate one to wage free speech war. Lorie Smith is wholly within her rights to advocate her views not just by writing a book, but by refusing to serve a customer, by firing an employee, by declining medical coverage -- you name it. And her opponents in turn can advocate their views by boycotting her business, picketing her house, urging her friends to ostracize her -- a war of all against all, with no zones of safety.

We could go further still. In a true free speech total war, if one "persuades" government to punish other speakers for their views, well, one just won a battle of free speech over those parties who oppose such measures (the dissident voices are, of course, free to shout their complaints as they're hauled off to jail, and the majority faction is in turn free to punish them further for their insolence). Nothing is off the table, everything is fair game, when it comes to ideological battles. Even if one can't quite follow me in seeing how express government punishment could be a form of extreme(!) free speech, the point is clear enough even if one takes everything but official de jure censorship off the table (as in the preceding paragraph).

Of course, this doesn't look much like "free speech" as we typically understand it. Much of the impetus of what is sometimes called "free speech culture" is to remove, less certain topics from discussion, but certain domains from encroachment in ideological battles. Ideological fights should be fought in the arenas of ideology, they should not normally spill over into who one employs (in positions that are not themselves expressly ideological) or who one is friends with or what businesses one patronizes. Even recognizing the pressure that can be placed on "normally" (or "expressly ideological"), the point is generally reasonable enough.

Consider a world where 303 Creative came out the other way. Someone with Lorie Smith's views continues to hold those views, in private, but as a business owner she dutifully follows the law and serves all her customers as equals. If someone pulled out her private beliefs (shared on Facebook, perhaps), and said "don't patronize this homophobic website designer", that would by many be viewed as a more "standard" case of problematic cancel culture. We might say in that circumstance that taking one's ideological opposition to Smith's views -- however justified -- and bootstrapping them onto whether to hire her as a web designer moves the ideological contest into a problematic domain. To be sure, I can absolutely understand the counterargument: that to give a homophobe money is to "normalize" her, to say her views are "okay", and it is entirely proper not to cooperate in that normalization. And it's not hard to think of cases at the margins where that counterargument may well carry the day. But if it always does, if there is no space between "view I disagree with" and "view whose adherents must be attacked along every possible front," that to me is a very unpleasant place to live in. As I wrote in my 303 Creative post:

One of the virtues of public accommodations law is that it dissipates, under normal circumstances, the inference that basic business transactions are expressive. I very much prefer a world where the bakery that bakes a cupcake for a client isn't seen as sending some sort of message of approval towards the client and the client that eats the baker's treat isn't sending a message of approval toward the baker (beyond "this cupcake is delicious"). That, to me, seems a far more pleasant space to live in than one where every turnip and widget we buy or sell can be taken as some sort of sweeping moral approval for our business partners.

Long story short: Yes, it's true that one can gain ideological victories by not limiting ideological contests to ideological arenas -- attacking them in their profession, their hobbies, their personal life, at every angle. But that world is a very nasty world to live in. Even if we think we might have to do that some of the time, it's very bad if we feel forced to do it all of the time. When social forces move us toward that world -- a free speech total war -- they are moving us towards a deeply toxic and oppressive social milieu.

All of this is lead in to Osita Nwanevu's column this week which, to some extent, endorses "free speech total war" position when it comes to the Israeli/Palestinian conflict and in particular campus discourse thereto. In contrast to the normal "free speech" position which suggests that we should protect advocacy of all sorts of views on Israel/Palestine, across the ideological spectrum, Nwanevu pivots sharply in the opposite direction: Progressives shouldn't stop trying to censor "bad" speech on campus, and should accept in turn that they will sometimes themselves be censored. "Students, academics, administrators, and outside influencers with different views will naturally clash and compete. In the end, some institutions will wind up more progressive or more conservative, [and] some institutions will be more or less tolerant of criticisms of Israel." Both "sides" should be free to wage ideological war on the other, and let the chips fall where they may.

The more workaday "free speech" position on this issue, the one Nwanevu is contesting, holds something like the following: (1) campus administrators should not punish or obstruct university speakers on the basis of their views, no matter how repellant (the prohibition on de jure censorship); and (2) non-administrative actors should largely limit the domains in which they oppose speech they disagree with to appropriate ideological channels (the norm against "cancel culture"). The former lays out, e.g., why one shouldn't prohibit a "bad" speaker from giving a talk on campus. The latter explains why its problematic to, e.g., refuse to hire an undergraduate for a summer internship because one didn't like their column in the campus newspaper.

Both prongs of this position have come under tremendous strain over the past few months(/years). The first position has come under regular fire from various campus actors who demand that bad speech be formally punished -- in the cases of the Milos, the Ben Shapiros, and what have you, but more recently and ironically against the SJP-types. The second position has been said to be under siege by proponents of "cancel culture" who don't just disagree with X Y Z views but insist that their proponents must be fired from their jobs, ousted from campus clubs, and be viciously ostracized online; and likewise is remanifesting when pro-Palestinian students see their employment offers revoked and their likeness plastered on placards declaring them antisemites d'jour.

A popular argument here is that this is the chickens coming home to roost: leftists loudly decried both traditional free speech and free speech culture, and are now reaping what they sowed. Nwanevu takes aim at this account, however:

It is not at all obvious, actually, that defenses of Palestinian resistance, particularly armed resistance, and criticisms of Israel—which has long been neigh-untouchable in mainstream political discourse—would have been more well-tolerated in a world where the campus controversies of the last decade hadn’t happened. We likely would have seen the very same pressure to support Israel after Hamas’s attack; as such, the speech climate likely would have been just as stultifying.

To believe otherwise is to invest fully in an odd precedential logic that regularly leads minds astray in these debates—those who use and abuse power are not always groping around for actions in the past that might justify their actions in the present. Reality is not a judiciary. And believing otherwise gives agency and responsibility over to whataboutism. Israel’s defenders and the right point to campus progressives, progressives might rightly say that conservatives and reactionaries suppressed left-wingers on campus first during the Cold War, defenders of Cold War conservatives might allude to the Soviets and the gulag, defenders of the Soviets might reference the repression of left-wing activists and thinkers by reactionary governments, and on and on backward in time to some creature of the caves who first realized that a club to the head was a reliable way to end arguments.

There is both more and less to this argument than it appears. On the one hand, I think Nwanevu is clearly right that the "precedential" bulwark against censorship would always be one whose robustness would be limited. "Reality is not a judiciary" indeed, there are always counter-precedents to point to, and everything we know about free speech suggests that there are far more fair-weather friends who are perfectly happy to demand freedom for me and censorship for thee than there are truly committed free speech ideologues who may, regrettably, falter in their commitments due to their opponents' hypocrisy. I agree that no matter how fastidious campus leftists may have been regarding free speech in 2022, it would not have stopped some people calling for the censorship of certain pro-Palestinian views in 2023.

That said, I also think Nwanevu is understating the degree to which the progressive development of free speech institutions is serving as a genuine bulwark against more censorial impulses, even now. Much as I think the levels of antisemitism on campus are overstated by alarmists even as they are no doubt real; it also must be said that the degree of censorship directed towards pro-Palestinian advocacy is simultaneously real and overstated by alarmists as well. Everything is a matter of margins: the question isn't whether commitments to free speech would eliminate all calls for censorship (or even successful instances of censorship), it's whether they are comparatively better at providing protection than alternatives.

In that vein: it is frankly absurd to contend that "criticism of Israel" is or has been "well-neigh untouchable" in campus politics. Take your average academic open letter savaging Israel signed by 1000 university professors, and 99.98% of them will not experience any tangible administrative blowback whatsoever. There's a ton of pro-Palestinian speech that does not and should not get any no pushback at all, and that's largely attributable to free speech commitments working.

Even looking at the list of exceptions proves the rule. Students for Justice in Palestine got targeted after it called the October 7 massacre a "historic win" that would augur a righteous campaign whereby Jews would be ethnically cleansed from Israel (yes, they did). Norman Finkelstein was denied tenure after writing a book titled "The Holocaust Industry". One can (like me) think that views like these are nonetheless protected while also zeroing in on exactly what is triggering the censorship -- not "pro-Palestinian speech" generally, but whooping and cheering a mass rape campaign specifically, or stating that Holocaust remembrance was an industry Jews exploit for profit, specifically. If that speech is coterminous with "pro-Palestinian" speech, that's a far more searing indictment of the field than I could give. And the notion that a more stultifying free speech environment than what we're seeing now is impossible to imagine -- well, I don't think it takes much in the way of imagination at all.

All that said, Nwanevu deserves credit for being willing to pay the piper. In the free speech total war "clash" between various stakeholders, sometimes, progressives will lose, not just in the realm of ideas, but lose quite tangibly -- their jobs, their social positions, their livelihoods. If one wants to extract those costs on others, one has to accept them for oneself.

Taking the freedom of institutions seriously in this way is not without costs for progressives. Bill Ackman and the captains of Wall Street do, in this framework, have the right to bar pro-Palestinian activists from employment at Scrooge McDuck Capital. The purges we’re seeing now are not incompatible with sound liberal principles—advocates for the Palestinian cause will not find refuge in them or in a fuzzy speech maximalism defined and defended inconsistently by most of its own proponents.

[....]

The only recourse is politics—the sturdiest argument against the repression of those speaking for Palestine isn’t that institutions and the billionaires and propagandists pressuring them don’t have the right to try suppressing Israel’s critics but that the Palestinian cause is substantively just, and Israel’s defenders are backing a senseless and immoral war, a stance more and more Americans are coming to agree with.

The "Scrooge McDuck" shot is a bit cowardly -- not because Ackman deserves any special deference, but because right after admitting that it's fine for pro-Palestinian activists to be subjected to the full blast of modern cancel culture it then slyly suggests that the only actual "costs" they might face are withdrawal of opportunities a good cadre member shouldn't desire anyway. The reality is far worse: the costs we're talking about aren't just loss of a chance to engage in rapacious vulture capitalism; they extend to every nook and cranny of the good life, every hobby and professional ambition a young person might have. That's what's on the table here -- for everyone, on both sides. The whole point is that Bill Ackman and SJP are equally entitled to pursue their ideological agenda by any means necessary. The end game, so bloodlessly described as "some institutions will wind up more progressive or more conservative", is better described as "ideological dissidents will be ruthlessly hounded out of their places of study, of worship, of employment, and of respite" -- dozens of the most caricatured version of Oberlin College being paired with countless New Colleges of Florida. Maybe we might think that, once the dust settles, everyone will be happier sorted into their neat ideological bubbles. But the transitional costs of successfully cleansing out the minorities will be monstrous -- a Tiebout sorting of the most vicious kind. And that really should be an intimidating proposition.

Why does Nwanevu nonetheless endorse going down that road? One possibility is that he doesn't truly believe the war will be as total as he's letting on. But another possibility is that he thinks that, when the dust settles, his side will win. The momentum is on their side. As many of "his" people will have their lives ruined by pro-Israel cancellation, he believes pro-Palestinian cancellation will be able to ruin even more. Is he right? I'm not as sure as he is about who would end up prevailing in a true free speech total war. But I do know that the casualty count will be staggering.

Like in real war, the constraints on free speech total war are fragile. The appeal of total war isn't pure sadism; it genuinely gives one a greater chance to win; it allows one to gain ground and overrun strongholds that otherwise might seem impregnable. But of course, that means that if one side indulges in it, the other must respond in kind -- a vicious circle to a world where everything is fair game and no one and nowhere is safe. And whatever marginal benefits one side or another might get in the conflict, the absolute costs are catastrophic. There's a reason why after World War II we labored as mightily as possible to ensure that a war like that never occurred again -- the world barely survived one war of that degree of fury, and it was far from clear it could survive a second.

I am inclined to think similarly towards the concept of a free speech total war. Of course, one way of reading Nwanevu's essay is believing that we're already in a world of free speech total war, one impressed upon progressives by conservatives, and they're only playing the hand they've been dealt (indeed, he even alludes to 303 Creative making similar points to what I made in my introduction). As alluded above, I don't think that's true -- I think we're actually quite far from a free speech total war, and we should be very leery about removing the guardrails keeping such a war at bay. A true free speech total war would be cataclysmic, disastrous, and, importantly, would look nothing like even the decayed and damaged free speech culture we have now. It would be far, far worse. We should not run eagerly towards it.