"Can You Be A Zionist Feminist? Linda Sarsour Says No." blares the headline of

The Nation. The Jewish press dutifully followed their lead, writing

"Pro-Palestinian activist: Support for Israel and feminism are incompatible." And so I thought "well apparently Sarsour's experiment with treating mainstream Jews respectfully has come to an end."

But dig a little deeper and ... well, it's confusing. Because if you actually read

The Nation interview, Sarsour never actually takes the position ascribed to her in the title. Now to be clear, she doesn't disavow it either. It's just ... not what she was asked, and not what she answered. Indeed, just compare the title and the subtitle:

Can You Be a Zionist Feminist? Linda Sarsour Says No

The prominent Palestinian-American feminist responds to claims that anti-Zionism has no place in the feminist movement.

You'll notice that these are two very different statements -- the first affirming that

Zionists have

no place in feminism, the second affirming that

anti-Zionists do have a place in feminism. Now, they could be reconciled: One side says Zionists, but not anti-Zionists, can be feminists; the other side saying anti-Zionists, but not Zionists, can be feminists. But this of course obscures a median position, which is that

both can be feminists -- or, more conditionally, both can be feminists if they meet certain qualifications regarding respect for all women (including those women whose rights and security are often thought to be undervalued by the movement in question).

So what position does Sarsour take? Is she saying that yes, anti-Zionists have a place in the feminist movement? Is she saying that no, Zionists have no such place? Is she restricting her critique to "right-wing Zionists" (Sarsour actually never speaks of "Zionists"

simpliciter, only "right-wing Zionists")? Or is she saying something different entirely, namely that Israel is a country, which does things criticizable, and therefore a feminist movement has to be open to criticism of Israel?

It's entirely unclear, and that unclearness is I think primarily attributable to

The Nation. I honestly

don't know if

The Nation understands there is a difference between saying Zionists are categorically barred, saying that anti-Zionists should not be excluded, and saying that a feminist movement will sometimes entail criticism of Israel. These clearly distinct concepts are so consistently run together that I really have no idea if

The Nation grasps that they're not the same thing. And so while it's entirely plausible that Sarsour does hold to the hardline position ascribed to her in the title,

The Nation ends up obscuring more than it illuminates because when it comes to matters like Zionism, anti-Zionism, and Jewish inclusion,

it's really, really not good at its job.

None of this is to say that there aren't elements of what Sarsour does (clearly) say which can be critiqued. Take her statement that "

anyone who wants to call themselves an activist cannot be selective. There is no country in this world that is immune to violating human rights." Perfectly defensible in the abstract, but it elides the reality that there is in fact there is in these movements in fact quite a bit of "selectiveness." The

Women's Strike Platform's characterization of the "decolonization of Palestine" as "the beating heart of the movement" is the

only international controversy to gain any mention anywhere in the document (the reference to Mexico is, in context, clearly about American actions, not Mexican ones). It's like Curtis Marez's famously blithe defense of singling out Israel for boycotts -- "one has to start somewhere." It's a far less effective retort when one seems to end there too.

Still, it is quite right in principle that a feminist must be an advocate for all women, and a critic of all policies (national or otherwise) which act to exclude women. And I'll go further: Zionism is a diverse movement with many streams, including ones which are liberal in the criticism of malign Israeli policies and insistent on securing Palestinian equality (this is one of the reasons why a flat exclusion of "Zionists" from the feminist pantheon is unjustifiable). Yet it is undeniable that, in its

primary political manifestation (that is, as state policy), Zionism has frequently resulted in severe injustices to Palestinians (men and women alike), of which the continued denial of Palestinian self-determination is only the most severe. It is not fair to impute that to all Zionists. It is fair to ask that persons who call themselves Zionists grapple with this history and practice in a way that demonstrates serious commitment to rectifying it.

Yet critically,

the same goes for anti-Zionists. They, too, cannot be "selective"; they, too, must be open to critiques about countries and movements and practices that have served to oppress. And in doing so, they too must stand for all women, including Jewish women, including Jewish Israeli women. Anti-Zionism, too, has its gendered oppressions; its moments and practices where it leverages the vulnerability of Jewish or Israeli women or explodes into grotesque violence. We remember, after all, the feminist lawyer in Egypt who reportedly endorsed rape as a tool of anti-Zionist resistance; extolling to the Israeli women across the border

"leave the land so we won't rape you." And today offered a particularly vicious illustration of the intersection, as Ahmed Daqamseh -- a former Jordanian soldier who massacred seven Israeli eighth-grade girls visiting his country on a field trip --

was released from prison. Upon his release, he told reporters that "The Israelis are the human waste of people, that the rest of the world has vomited up at our feet. We must eliminate them by fire or by burial." When deciding whether someone who helped blow up two more Jews in a supermarket should take on a leading role in this new feminist movement, this practice should matter.

The easy move here is to dismiss the above cases as aberrations or, supposedly more damningly, as disconnected from power. But here, too, we must note that, while anti-Zionism is a diverse and variegated movement in how it manifests in academia or social circles, in its

primary political manifestation as state policy it has frequently resulted in severe injustices to Jews (men and women alike). Anti-Zionism as a

political form claims as its most decisive political action not the liberation of Palestinians but the mass oppression and expulsions of Jews from Middle Eastern countries, undertaken explicitly under an anti-Zionist banner. If it seems like anti-Zionism-as-politics does not currently manifest in this form of direct, unmediated danger to Jewish lives, that's primarily because there are virtually no Jews left in the locations where anti-Zionism manifests as politically dominant. Again, this does not mean that all anti-Zionists endorse these acts. It does mean that persons who call themselves anti-Zionists must grapple with this history and practice in a way that demonstrates serious commitment to rectifying it. Because feminism really

cannot be selective, it cannot be concerned with the fates of only the right sorts of women.

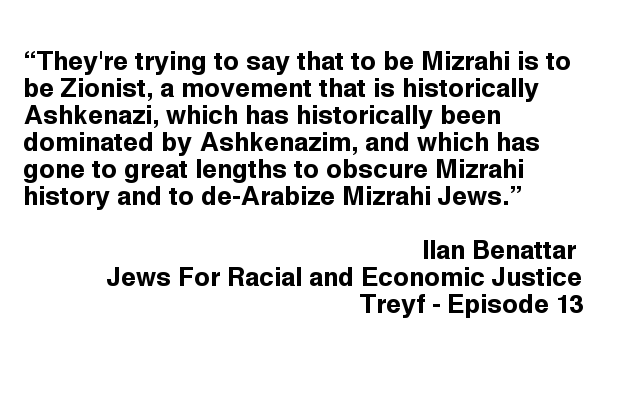

We all have our blind spots and things we need to work on. It is perhaps relevant, then, to mention the occasion where I first encountered Linda Sarsour. It was

after she spoke at the First Annual Jews of Color conference, telling Mizrahi (Middle Eastern) Jews that "We will welcome you and embrace you in your full complexity. We’re waiting for you at the Arab American Association." JIMENA (Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa)

promptly asked her if she would be willing to partner with them, a predominantly Zionist organization.

Sarsour proceeded to ignore them entirely. Some complexity. We weren't off to a good start.

Yet despite all of this and as cutting as I might seem here, it is important to emphasize also that there is a fair amount of rhetoric ginned up around Linda Sarsour that is -- without mincing words -- complete bullshit. The

most grotesque is that which invokes her support of "Sharia law", using language that echoes in form and tone efforts to demonize observant Jews by reference to the most extreme iterations of

Halacha (I can look favorably upon Jewish law and still find the

Agunah doctrine execrable; likewise Sarsour can speak positively of Sharia while not endorsing crediting women half that of men. Only antisemites and Islamophobes think otherwise, or think it is fair to ascribe monolithic -- and reactionary -- uniformity to a pluralistic and contested legal tradition).

Likewise those who accuse her of opportunism when she helped raise funds to restore

desecrated gravestones at a Jewish cemetery in St. Louis. The raw fact is that she came through -- in deed, not just word -- when those Jews needed her, and I can be critical of problematic elements of her political profile without needing to look a gift horse in the mouth. Ditto her behavior as Women's March co-organizer, where in contrast to her flamethrower reputation she

did not act in a way that would have functionally excluded the vast majority of Jews from participating (indeed, it was these steps that made what I initially took to be her statement to

The Nation something disappointing, as opposed to predictable).

In any event.

Palestinian women are women. Israeli women are women. Muslim women are women. Jewish women are women. And,

since we ought to be intersectional about it, Middle Eastern (Mizrahi) Jewish women are women. A feminism which does not stand with, protect, uphold, promote, elevate, and engage with all of these women is a feminism that fails. Because Linda Sarsour is absolutely right: feminism cannot be selective.