Last week, I spent some time at the eye doctor to address periodic swelling, irritation, and pain in my left eye. This happens periodically, but it got especially bad during my trip to Florida (to the point where airline attendants asked if I needed paramedics to meet me once we landed). The doctor was quite nice but suggested that incidents like this are

a symptom of my keratoconus worsening and there probably wasn't much to be done at this point other than hope it doesn't happen too often and ride it out when it does.

I say "at this point" because at an earlier point there was something to be done -- a surgical proceeding called corneal cross-linking. Cross-linking surgery doesn't "fix" keratoconus, it just stops further deterioration, but since keratoconus is a degenerative condition that's no small thing. I was slated to get cross-linking surgery while at Berkeley, but at the last moment my insurer denied coverage as not medically necessary since I could still see with contact lenses. Again, remember that what cross-linking does is stop degeneration -- that is, the surgery would preserve the status quo where I could see with contact lenses -- so the fact that I currently could see with contact lenses is exactly why the surgery was being recommended to me. Nonetheless, even though the surgery had been scheduled for months, the insurer issued its denial just a day or two before, giving me essentially no time to appeal or gather additional medical information to support why the surgery was, in fact, necessary.

Several years later (now in Portland), I was able to get the surgery -- but only in my right eye. My left eye had, in the intervening years, deteriorated to the point where it was no longer a candidate for the procedure. And that deterioration is likely permanent, and (given the periodic swelling etc.) possibly still ongoing. My doctor said that if things continue to get worse in that eye, the only real treatment option available is a full-blown corneal transplant -- quite a bit more intense (and expensive) than cross-linking would have been, and not something I'm especially excited to pursue. There's not even the karmic satisfaction of the insurer having to pay more, because I'm on different insurance now compared to when the surgery was initially denied!

My experience is, of course, not uncommon. We've all been swapping stories on this subject prompted by the murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. My case is not to the degree of being denied life-saving care, but permanent vision loss in an eye is not exactly frivolous either. Like many Americans, I have persistent ambient anxiety about what would happen if I faced a major medical crisis, and that anxiety is less about the crisis itself and more wondering in what ways will my insurer try to screw me over in my most vulnerable moment in order to financially ruin me.

There are very, very good reasons for Americans to loathe their health insurance companies. But even still, it is alarming how many people are outright thrilled to have witnessed a street murder. The cause of this excitement is, no doubt, in significant part justifiable fury at the injustices health insurers wreak on regular people. But that more systemic explanation I think has to be cut with acknowledgment that a significant portion of people seem to be excited at the prospect of being justified in cheering a murder. They are luxuriating in this feeling of justified schadenfreude, and are encouraging others to feel similarly, and are hoping to feel it again and again.

No matter how one identifies the cause, such a situation is not a sign of a healthy society. For me, there were eerie echoes of the days after October 7, where we also saw too many people be not just thrilled at seeing Israelis murdered, but thrilled at their mutual, collectively reinforcing justifications at why they were right to be thrilled. Certainly, Thompson was far more directly complicit in injustice than a group of teenaged concertgoers, whose "complicity" was basically being Israelis full stop. But to the celebrators, this is a difference of degree and not kind -- they labored hard to establish why being Israeli was a form of culpable complicity for which the proper punishment was death and the proper affect was a hearty cheer. And that effort to stretch so one can properly enjoy the murder is powerful evidence that the desire to enjoy murders is the actual driving motivation, with the political or strategic apologias just epiphenomenal window dressing. How far down the pecking order at UHC is it warranted to be excited at extermination? To the adjusters? To the HR professionals? To the janitors? We all know the Tumblr accounts who would rush to point out we should cheer not just the death of the Himmlers but every German Nazi, top to bottom -- so why not apply that logic to UHC? Or to Israel? Or to any other institution complicit in systemic injustice -- a category which can include without too much in the way of struggle every institution? (This was one of the lessons of The Good Place -- while everyone has an obligation to try to do the right thing, overindulgence in "complicity" arguments makes everyone guilty and places everyone in hell).

The terrible realization many of us had, and are having again, is that for many the orientation towards Israel/Palestine or the American healthcare system isn't "let's create a just political structure for all" but rather "I want to see the right people be hurt," and the thirst for the latter is what drives the nominal political commitments rather than vice versa. Even where one can sympathize with the causes, this sort of outlook never leads anywhere good; more often than not, it's just people coming up with stories for why they should be permitted to revel in the misery of others. As a species, we should know well that our problem is not that we are too skittish about justifying brutality and violence, and so we should be hesitant about any political momentum which takes the form of accentuating and accelerating a popular desire to enjoy murder.

It is no answer to point out the many, many more people whose lives have been ruined by unjust insurance denials (UHC has the highest denial rate in the country, denying a full third of all filed claims). For one, anyone who reads a story about one of these denials and lets out a whoop and high fives would be a bad person too. More fundamentally, I also return to one of the most outstanding articles I've ever read, Robin West's "Sex, Law, and Consent," which does a superb job explaining how direct interpersonal injustices are qualitatively different than "systemic" ones even when the latter cause greater tangible loss than the former. We experience being robbed or burgled differently from being on the receiving end of wage theft, even if the latter might actually take more dollars from our pocket; West extends this analysis to how we think of rape vis-a-vis the broader suite of patriarchal norms which regularly generate "consent" to sexual activities that are not truly or enthusiastically desired. Again, this doesn't mean that UHC's conduct in the healthcare system isn't an example of serious injustice -- it is, just like wage theft is and just like structural sexism is -- but the point is that we're not simply delusional in viewing street murder as qualitatively different notwithstanding the fact that it is but one dead body.

I say all this because there is not, or should not be, a tension between "the murder of Brian Thompson is bad" and "we are obligated to create a more just and humane healthcare system that is not liable to the exploitations and predations of entities like UnitedHealthCare." Anxiety about insurer-driven financial ruin notwithstanding, and direct experience with insurer manipulation causing permanent medical injury notwithstanding, I never wanted Brian Thompson to die, and I cannot relate to thousands of internet strangers who did want him to die. What I want is for our health care system to work for us and to take care of us. That's all. My first response to Thompson's murder was to write:

The murder of UnitedHealthcare's CEO is outrageous. We as a society must do everything in our power to ensure that a tragedy like this never occurs again. If that means implementing national universal healthcare so that anger over a failing private system isn't displaced onto violence, so be it.

And while yes, that was intentionally snarky, I also meant it with total earnestness. We should hate murder. And we should commit ourselves to creating a just healthcare system that doesn't generate justified seething hatred amongst ordinary Americans.

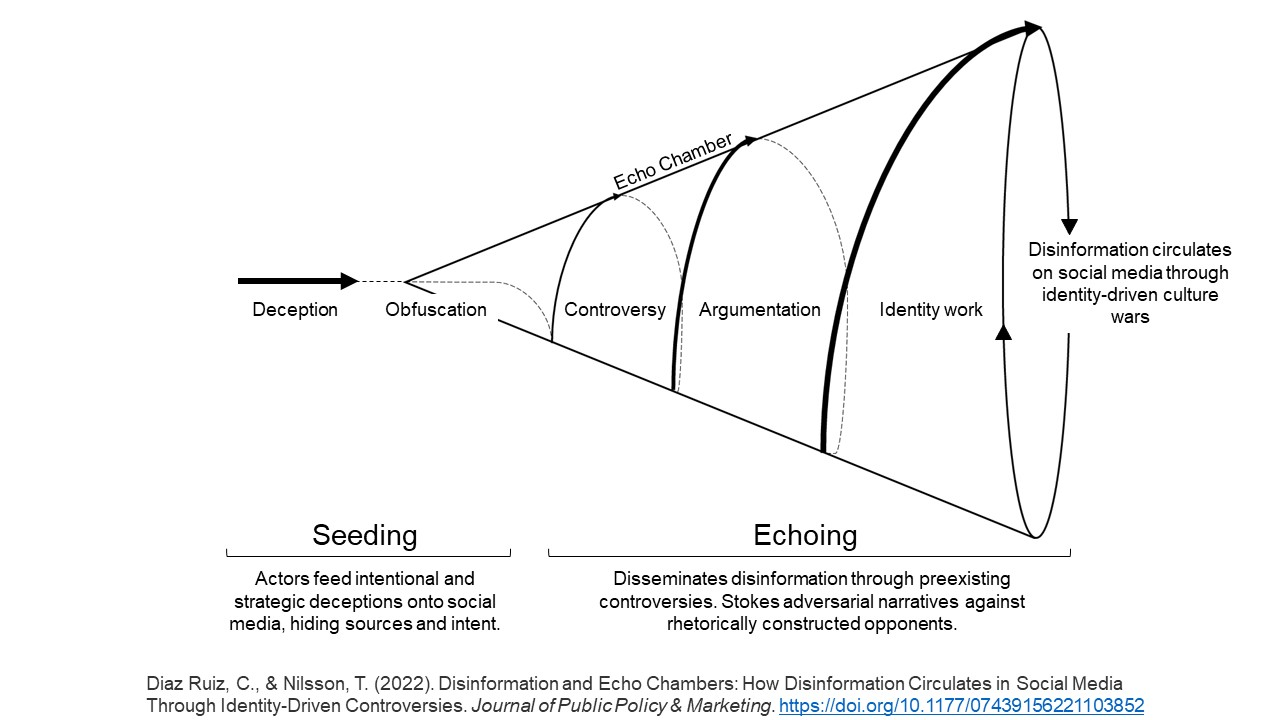

Yet here we see another element of our despairing time, which is that the proof is in the pudding in terms of what drives social change. Just like it may be sadly true that manipulative echo chambers are a more effective political strategy that earnest and honest engagement with people of diverse political views, it may be sadly true that violence and social disruption are able to drive necessary political change where persuasion and law fail. It is a bad precedent when we let terroristic violence drive even salutary social change, and the lesson to draw from that is to make salutary social changes without being prompted to do so by terroristic violence. And if we can't learn that lesson, then I'm at a loss except to say that it inherently puts us in a very grim place, and nobody should be excited to live there.

I have no answers here. But I again cannot help but feel that it is fundamentally unhealthy when people feel, and are encouraged to feel, excitement over murder. For too many people, the murder of Brian Thompson isn't about murder or even about generating justice in the healthcare space. It rather is an opportunity to enjoy the spectacle of a murder, and feel righteous in doing so. That instinct is one we should be very wary about letting flower unchecked, in ourselves or in others.

.jpg)